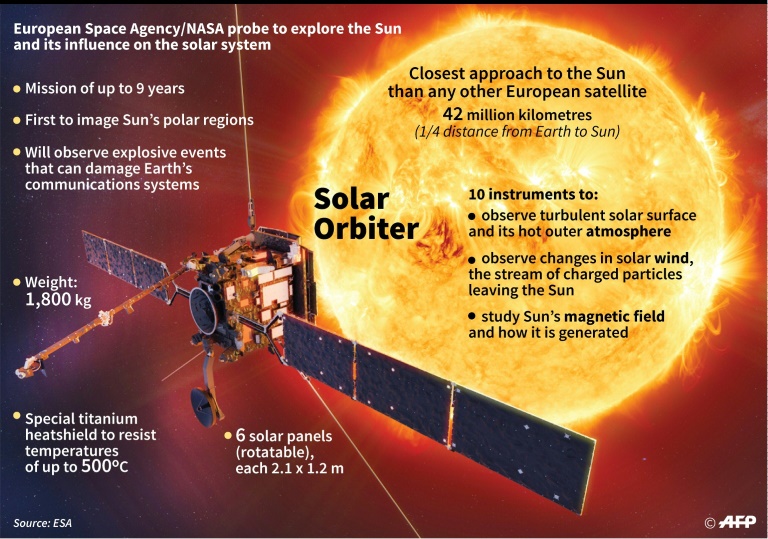

The Solar Orbiter mission to explore the Sun. AFP

The European Space Agency will embark upon one of its most ambitious projects to date on Sunday when its Solar Orbiter probe launches from Florida’s Cape Canaveral bound for the Sun.

The craft, developed jointly with Nasa, is expected to provide scientists with unprecedented insights into the Sun’s atmosphere, its winds and magnetic fields.

It will also garner the first-ever images of our star’s uncharted polar regions.

After a fly-by of Venus and Mercury, the satellite is set to hit a maximum speed of 245,000km/h and settle into orbit around 68 million kilometres from the Sun’s surface.

Packed on board will be 10 state-of-the-art instruments to record myriad observations that scientists hope will unlock some clues about what drives solar winds and flares.

Mission director Anne Pacros said the experiment was designed to “understand how the Sun creates and controls the heliosphere” – the giant bubble of plasma that surrounds the Solar System.

Solar winds and flares emit billions of highly charged particles that impact planets, including Earth. But the phenomena remains poorly understood despite decades of research.

“Solar wind may be slow or fast, and we don’t know what causes this variability. Is it one wind that varies or is it several?” said Miho Janvier, from France’s Institute for Space Astrophysics.

“It’s one of the mysteries we hope to solve.”

The results could have far-reaching impacts for Earth.

Charged particles carried on solar wind are most often experienced on our home planet when they strike Earth’s magnetosphere, producing spectacular Northern Lights displays at upper latitudes.

But Matthieu Berthomier, a researcher at the Paris-based Plasma Physics Laboratory, said the impacts of solar wind went far beyond the North Pole.

“Solar winds disturb our electromagnetic environment. It’s what we call space weather, and it can affect our daily lives,” he said.

The largest solar storm on record hit North America in September 1859, knocking out much of the continent’s telegraph network and bathing the skies in an aurora viewable as far away as the Caribbean.

Solar ejections can also disrupt radar systems, radio networks and can even render satellites useless, though such extremes are rare.

“Society increasing relies on what happens in space and therefore we’re more dependent on what the Sun is doing,” said Etienne Pariat, a researcher at the CNRS observatory in Paris.

“Imagine if just half of our satellites were destroyed,” added Berthomier. “It would be a disaster for mankind.”

Orbiting relatively close to the Sun, Solar Orbiter will be exposed to sunlight 13 times stronger than that reaching Earth.

It has been constructed to withstand temperatures as high as 500 Celsius and its heat-resistant structure also protects its instruments from extreme particle radiation emitted from explosions in the Sun’s atmosphere.

Experts said the mission could help better modelling of solar winds by directly monitoring their source.

“A solar storm can hit us within a day or two [of happening],” said Berthomier. “We could, therefore, have time to protect ourselves by turning off the electrical systems of satellites.”

The mission is due to blast off from the Kennedy Space Center at 2300 local time Sunday and is set to last up to nine years at a cost of some $1.64 billion.