Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in 2021. Hong Menea

Over 11,000 messages were carved or written on the walls of Security Office S-21 by detainees according to a survey of them done by the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (TSGM).

TSGM posted to social media on August 1, stating that many of the detainees carved or drew words and pictures on the walls of their cells while they were detained there from 1975-1979, the period when Cambodia was under the control of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge.

The museum said that the contents of the messages frequently expressed the detainees’ emotional distress and despair, especially those who were aware that they were very likely to be executed soon.

“The museum has found 11,443 inscriptions as text, symbols, drawings, paintings, graffiti and other imagery left on

the walls, stairs, pillars or floors of each building. We recorded each of them and added them to the existing database of 1,136 inscriptions,” the TSGM said in a statement posted to Facebook on August 1.

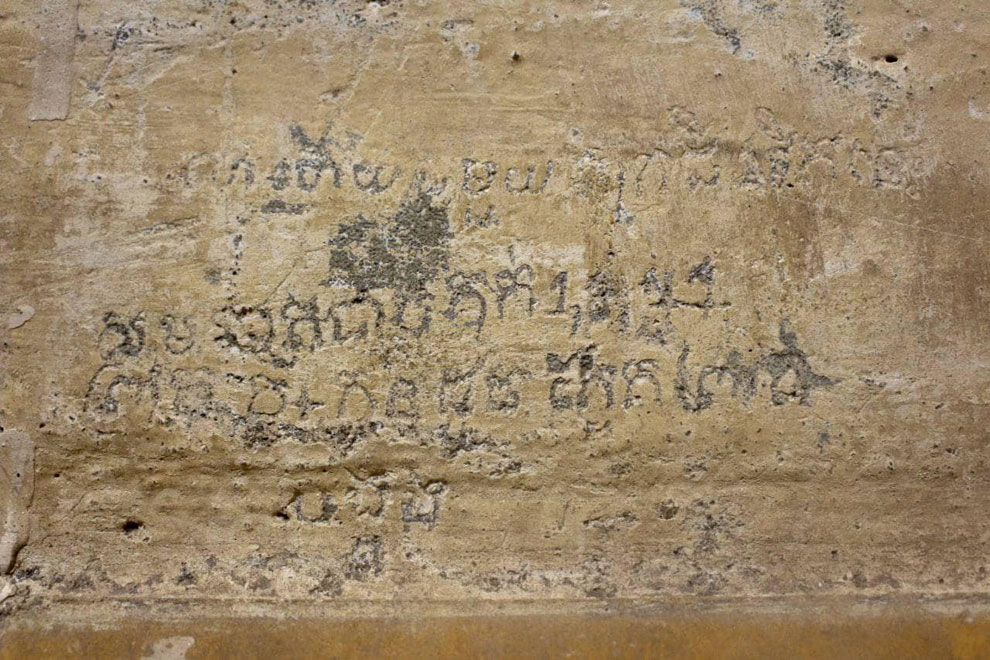

It said the contents consisted of everything from mathematical formulas, Khmer history lessons, slogans, political messages, dates of detention or number of days in detention, the names of detainees, the national symbols of Democratic Kampuchea, pornographic drawings, love poetry, and in some cases the victim’s last words or messages for others, among others.

“Goodbye to this life! I was imprisoned on the 1st of August ‘77 – Comrade Chhat,” said one inscription written by a Khmer Rouge cadre who was executed by the regime in one of its many internal purges, according to the museum.

Victim's messages written on the wall in Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

S-21 was overseen by Kaing Guek Leu, also known as Duch, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2012 by the Supreme Court Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) and died in 2020.

The ECCC determined that at least 18,133 prisoners were executed at S-21, which is located in central Phnom Penh and was a school prior to the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power.

In 2009, the archives of TSGM were recognised as “World Documentary Heritage of International Significance” and were inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

“That was a historic moment for the archives of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, which was created in 1979. Due to this recognition, the museum has received assistance in document conservation because these historical documents are recognised as containing significance for humanity,” TSGM said in a statement.

TSGM’s director Chhay Visoth told The Post on August 1 that the museum had started recording those messages and carvings in 2016 by photographing them and entering them all in a database. Now, a new database has been developed to store and link all of the data and information related to S-21.

According to Visoth, visitors to TSGM, both local and international, pay little attention to the paintings, carvings, and writings on the walls made by the prisoners. He said some prisoners had made small scratch marks to keep count of the number of days they were there, perhaps 15 or 20 of them and then no more, most likely because of their deaths.

Some detainees simply wrote their names while others wrote declarations of loyalty to Angkar, a term that referred to the Khmer Rouge government, perhaps sincerely or perhaps in the hopes that it would save them.

“In Building C, we have noted that both prisoners and prison guards apparently got bored and drew pornographic picture and wrote sexually explicit words. We can tell when it was guards because they could write outside of their cells, but prisoners mostly wrote on the walls of their cells and often with leg-irons around their ankles,” Visoth said.

He explained that prisoners usually used their fingernails to carve or scratch on the walls, but some of the writing was found in pencil or carved with sharp objects.

According to TSGM, only 12 people were left alive at S-21 when the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (FUNSK) entered Phnom Penh in January 1979. Four of them were children.