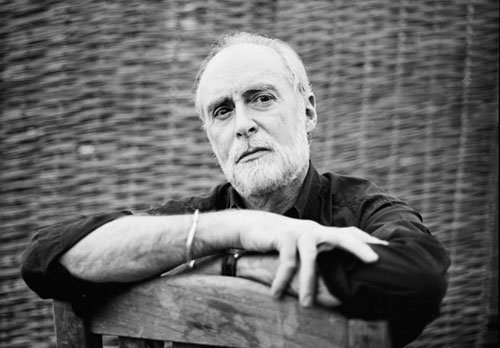

Sydney Schanberg witnessed the capture and evacuation of Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge while working as a reporter for the New York Times. After two weeks in the French embassy, he left the country, while his colleague, Dith Pran, was forced to join other Cambodians in the countryside. When the Khmer Rouge fell, Schanberg was reunited with Pran and wrote an article and book about his friend’s experience under the Khmer Rouge that was later turned into a film, The Killing Fields. Schanberg testified before the Khmer Rouge tribunal last week. Days later, he spoke with the Post’s Justine Drennan about his impressions of the trial, as well as those fateful years.

Editor's note: This is a longer version than appeared in print.

So what was it like testifying at the Khmer Rouge tribunal?

Well, I found it interesting because I’ve never testified in this kind of setting. And you know, in my life, having covered trials and so forth but not this kind of a trial, this was very different. It was new to me—therefore interesting. And everybody was sort of polite. I objected a few times about the way questions were put and so forth, but I really was very impressed by how organised it was. There weren’t any arguments or loud language or anything else like that. So I was impressed. And I congratulate those who are still doing it, though I guess it’s going to close down, or think people think it’s going to be closed, before long.

The interesting thing for me is that I spent so much time there, in Cambodia, thinking about how this all happened, and at one point in my testimony I did kind of summarise that—that it happened because of the other interventions. That is, the Vietnamese had permission (not admitted—in other words Sihanouk didn’t admit that he had given permission, but he had) to bring supplies in. And the Americans had been given permission to bomb the Ho Chi Minh trail. And, I think, as I testified, what happened after that is, when the Lon Nol group deposed Sihanouk (he was in France at the time) [US President Richard] Nixon and his advisor, Henry Kissinger, decided that an incursion of many thousands of American soldiers would come in and clean out the sanctuaries that the North Vietnamese had put together. Before, the war only touched Cambodia on the eastern border. And it wasn’t something that in the beginning sounded like the Khmer Rouge could take over the county. But once you spread it, you’ve got a real war on your hands.

I’m telling you this from my own experience because I was not fighting in the war in Cambodia—I was observing from very close up. You begin to wonder what your government is doing, and it’s not always pretty. So you know, in my own mind, how I look at what happened in Cambodia is what has happened through history. You know, small countries are used by powerful countries to get what they want, and nobody really wants to talk about that.

In any case, the tribunal didn’t focus on that. They were focusing on the leaders who had sanctioned or who knew about the killings and didn’t do anything about that. But I’m just telling you it was a different America from the country I was born into. It’s changed a great deal. Because World War II was a necessary war, and the Vietnam War was not a necessary war. But at the time, Washington was wallowing in the Domino Theory that if the North Vienamese were to win that war, it could spread all through Southeast Asia, and that hasn’t happened. And that was a Cold War thing.

I’m just telling you my frame of mind when I look at what happened in Cambodia, and it’s another thing that didn’t have to happen. So that was what I brought in when I came to testify—that’s what was in my mind.

And when they asked me to testify, I wanted to, because I felt that I had an obligation to tell what I saw, and of course, the defence lawyers aren’t going to like that. But it was a very good experience for me. And I feel that the tribunal was necessary. Took a long time getting there, but it’s very, very necessary for the history of Cambodia, that the people young now and were not alive during the war can go back and look and learn.

Beyond your own testimony, do you have thoughts about the recent proceedings at the tribunal?

When I saw Nuon Chea testifying, I understood why he said all the things he said—that they emptied the city because the Americans were going to bomb, and the Vietnamese might come in—but you know, while we were prisoners, or while we were in the French Embassy, all those days, at that period, the Americans were pulling out and had already signed a peace treaty with the Vietnamese. They were pulling out from their Embassy, they were evacuating. And the South Vietnamese government was being overrun. The communist soldiers had taken over Saigon, so why on earth did they imagine…both sides were occupied, you know, the communists were taking control, and the others, their opponents, were trying to negotiate with them so as not to be thrown in jail.

Nobody was talking about invading Cambodia. But I understand completely why he said those things, because he may have some fear and regrets. And he doesn’t want to be jailed or whatever. So I understand that as a human being, and I—I have no objection to him being punished. But I also have no objection to him saying foolish things because he’s frightened, or because he actually is sorry about it. But that doesn’t bring back the people who died.

You’ve been back to Cambodia since that time. What’s that been like for you?

I went back. I’ve been back a couple of times. And it was—how should I put it?—it reminded me of many things, and many of them were negative. People had died, friends of mine. One of my drivers was executed, we found out later, by the Khmer Rouge. And we don’t know what was the charge and what he was supposed to have done, what rule did he break, I don’t know. His wife told me that they came to their hut, the soldiers, and took him away, and didn’t tell them anything, and she never saw him again.

And a lot of people who had lived through it have been very, very hurt, meaning they stayed alive but they dreamed about all of this.

Somebody would be riding on a bike down a major thoroughfare and they would suddenly lose control and slide off and bang into a car parked on the curb. And I saw it enough times to know what happened: they were riding on their bike and thinking about what happened during the warm and saw in their memory, saw their mothers and fathers die, or sisters and brothers, and then suddenly boom they’d lose control of the bicycle. And so a lot of it was really very difficult for me. Not difficult, but disturbing. That’s probably pretty much gone now, and there’s a new generation, but it hurt to watch these people who were damaged and who had lost members of their family.

So, yeah, it wasn’t a vacation. I was writing a piece for a magazine. That’s why I was there.

When was that?

It was when the Vietnamese army was pulling out. We saw them leave, and I think the people were happy not to have more soldiers around, you know, other soldiers. But I don’t see any move toward democracy yet. Hun Sen is a strongman kind of ruler. I have no evidence, but the press has already reported several times where the evidence suggests that he had ordered his men to go and kill some political opponent or something. He’s a tough guy, and he says he wants to rule until he’s 90, that’s a long item from now, and then his son, he’s going to take over. So, you know, it’s not an encouraging scene, as a country.

Was there anything you felt you didn’t get a chance to mention in your testimony?

After the Khmer Rouge were pushed to the western areas by the Vietnamese army of 1979, certain things happened that were really very shameful, to me, about what my country was doing. For example, for several years after that, the seat at the United Nations was occupied by the Khmer Rouge, and not the new government. It was the United States who led the successful effort, that the seat in the United Nations building and the General Assembly was held by the Khmer Rouge, and not by the Hun Sen government which had been established by Vietnamese. And this was all part of the motivation by the presidency, the American presidency, or the Pentagon, or all of them, that the real problem was Vietnam. They wanted to keep Vietnam from being in the UN in the form of having created this government. And if a genocide had taken place, and it had, then what in the world are you doing by giving this seat to the people who committed it?

Not that I’m rooting for any particular country, but here I’m saying you know what they did, and it was a genocide. Just as an individual, I was very, very uncomfortable and critical of that. And eventually it stopped, eventually [the new government] got the seat, but it was several years. [Until then,] the flag of the Khmer Rouge was flying along with all the other flags of the countries in the United Nations. There’s a whole line of them in front of the Secretariat building of all the flags of all the nations in the United Nations. And that struck me as being as if after World War II we flew the Nazis’ flag outside the United Nations. It was insane and it was embarrassing. It was like rewarding the criminals with this seat.

But of course, in my testimony, I didn’t go into this. It’s not the subject of the trial. The trial is all about the killing by the Khmer Rouge. But the world is upside down at times—that’s the way world politics go. And at the time, in those few years that they held the seat, the Western nations, several of them, Australia, the United States, England, would have meetings in Thailand every couple of weeks to decide what supplies they were going to give to the [Cambodian] democracy movement. Trouble was, the democracy movement pushed into closely by the areas where the Khmer Rouge were still there. They weren’t holding Phnom Penh and they weren’t having a major drive or anything else, but a lot of those supplies got to the Khmer Rouge.

Inside the [US] State Department, the rule was that if you were traveling to a gathering of diplomats or officials from all the UN countries, that if you were in the American group, you weren’t supposed to talk to members of the Khmer Rouge. But this was never told to the American public. And the press made nothing of it. As a columnist at that time, I wrote about it, but the mainstream press didn’t go near it. Because I guess—I don’t know what they felt, but I know that lots of things that nations do are buried, and never spoken of again.

Contact PhnomPenh Post for full article

Post Media Co LtdThe Elements Condominium, Level 7

Hun Sen Boulevard

Phum Tuol Roka III

Sangkat Chak Angre Krom, Khan Meanchey

12353 Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Telegram: 092 555 741

Email: [email protected]