brief.jpg

From "Mission civilisatrice" to "Mission démocratisatrice"1? By Henri

Locard.

Cambodians are voting this Sunday, February 3, 2002 in commune elections

and most agree that the country will be taking a decisive step along the path to

democracy. But people are mistaken in believing that it is the first time ever

in Cambodia that the citizenry-men and women, perhaps-will be allowed to choose

freely their councillors and, in turn, their mékhums and their deputies. For

there has been quite a long history of grassroots democracy in Cambodia.

A short history of the Cambodian commune & the ballot system

In the old days, before the arrival of the French, and the signing of the

Treaty of Protectorate in 1863, the smallest administrative division was then

called srok and varied considerably in size, according to the population

density2. Notables gathered and chose from among themselves the village chief

and his deputies, serving as an informal body of councillors3. However, by the

19th century, those notables no longer played much of an official role and local

leaders were nominated by the authorities up above. Their main duties were to

collect taxes and maintain law and order.

With the French Protectorate,

a number of initial reforms were attempted in the days of King Norodom I

(1859-1904), but it was under the reign of his younger brother, King Sisowath

(1904-1927), that the modern khum was really created by the Ordonnance Royale

(O.R.) of June 5, 1908. Elections of mékhum and their chumtup (councillors) in

the srok were first instituted from signing of the O.R. of August 21, 19014.

Notables were to be elected by those who paid the personal tax (that is

virtually everyone-men and women), provided the election was afterwards legally

sanctioned by the District Chief or Chauvaysrok, himself appointed by the

provincial Cambodian Governor or Chauvaykhet.

These "universal

elections", as they were called, indeed took place from 1901 to World War II,

but those have never been general in the sense the February 3, 2002 polls are

nationwide. From 1901 tentatively, and more formally from June 5, 1908 in the

fourteen provinces, elections have occurred at different dates for each province

and later at different dates in each srok or even khum when the time or

necessity arose to organise new elections.

But one must admit that a

long investigation into surviving archives in both Cambodia and France would be

required to determine if those elections really benefited the ordinary Khmer

farmer. Did these polls really sow the first seeds of local democracy or were

they only a means for the coloniser to grasp hold of the entire territory, down

to every individual rice-grower and therefore tax payer? If we turn to

historians from both the French and the English speaking worlds they would tend

to answer negatively, while other authors simply ignore the importance of local

democracy and totally overlook the khum in their narratives. A brief

historiography of the Cambodian commune, since the abolition of "apanages5,"

granted to Palace dignitaries, is revealing.

On the French side, for

instance, in the classic French complete study of Institutions

constitutionnelles & Politiques du Cambodge by Claude-Gilles Gour, published

in 1965, in the heyday of the Sangkum period, one can read:

The

institution of bodies representative of the entire population was attempted

without much success at all levels of the Cambodian administration [...] - at

the village level first, as early as 1877, then by 1884 and 1908 texts, and

finally by the Royal Ordinance of 15 November 1925. Those are the main landmarks

in the institution of a local autonomy, modelled on the West at the communal

level. Unfortunately the author adds: ... a study of that institution would go

beyond our present preoccupations6.

Similarly, in Penny Edwards' recent

perceptive and informative study of Cambodia's Cultivation of a nation,

1860-1945, we fail to find any information about the birth of the modern

Nation-State at the local level. We read with great interest about early French

efforts to do away with patron-client networks in order to establish State-based

loyalties7, about the absence of the notion of a State operating outside of

personal relationships, about the regional character of traditional form of

government Mandarins8, about Western concepts of governance with its new

nation-centric orientations that inevitably modified this, but the Cambodian

commune itself is also absent.

This approach is in line with her academic

mentor, David Chandler, who, overlooked all details about the creation and the

organisation of the khum. He merely sweeps the question away by stating

peremptorily:

[In 1921], the French experimented with a "communal"

reorganisation of Cambodia along Vietnamese lines, only to drop it after a year

or so9.

Alain Forest, who restricts his study to the early years of

France's attempts at establishing a modern form of administration in the Kingdom

of Cambodia, that is the years from 1897 to 1920, comes up with a rather

pessimistic view of the French endeavour at creating democratically elected

communes. Paradoxically, he does so in spite of the subtitle of his PhD study of

the period: Le Cambodge & la colonisation française, Histoire d'une

colonisation sans heurts. By and large, he asserts that traditional village

chiefs, freely selected by local notables in the past, were replaced by a

universal suffrage that was alien to Khmer traditions. Since the main duties of

the khum authorities were to maintain law and order and collect taxes from all

and sundry, they tended to become policemen and tax collectors in the eyes of

their electors. So their position became almost untenable: were they the

mouthpieces of the people or representatives of the French colonial power?

What made things worse was that, geographically speaking, the new

Cambodian khum was not modelled on the French commune (as everyone claims), the

parish of the pre-revolutionary Ancien régime days in France. It embraced-and

still embraces today-a much wider administrative division that included several

villages around their pagodas, and therefore centuries-old communities. The

hyper-centralising Khmer Rouge liked that, for they soon replaced the smaller

village sahakor (their rural forced camps or collectives) by larger units based

on the colonial communes.

The nadir of negative assessment of French

attempts at establishing an administration that would extend to the heart of

Khmer society was reached in John Tully's Cambodia Under the Tricolour: King

Sisowath and the "Mission Civilisatrice", 1904-1927:

"As his sub-title

indicates10, Forest regards the Protectorate as basically beneficial for

Cambodia. This is a one-sided interpretation. Sisowath's Cambodia, in common

with Indochina as a whole at the time, can be described as a colonial police

state, ruled with an iron hand by a strict hierarchy of power with its apex in

Hanoi."

Fortunately, not fearing to contradict himself, John Tully

writes extensively in sharp opposition to this ideological stance (not to say

one that is out of place, after the totalitarian regime of "Democratic"

Kampuchea). He clearly details the sweeping modernising reforms brought by the

colonial administration and approved by the enlightened monarch. Tully noted

perceptively that if "the accession of Sisowath to the throne marked the

beginning of [the] golden age [of French presence]11 that was to last for four

decades, Cambodia had lost what sovereignty she had; the fiction of the

protectorate was a flimsy legal veil for the reality of the de facto colonial

rule. It is about the qualification of the very nature of this colonial rule

that one can be allowed to disagree. If Tully fairly lists the full amount of

the achievements of those forty years, he concludes that "the French [did not]

seriously challenge the traditions of absolutist rule12". Nothing could be

further from the truth. Even during the 23 years of Sisowath's reign, great

strides towards a constitutional monarchy had been made. The King had accepted

as a matter of principle (in the name of not only unavoidable, but even

desirable modernization) to give his approval to suggestions of the colonial

administration. His son, King Monivong (1927-1941) had a similar attitude. Under

young King Norodom Sihanouk, the country's first democratic constitution was

established in 1947, before the French were forced to hand back power on

November 9, 1953. By then, "Absolute Rule" had been terminated - officially,

that is.

To prove his point, Tully rightly points to the great weakness

of the educational field in colonial days (a weakness that was to be addressed

in Sangkum days), but totally failed to mention that it was under Sisowath's

reign that the commune, along with universally elected local councils, came

legally into existence. He did not mention these for a very simple material

reason, one can presume (apart from his ideological looking-glasses). He looked

carefully at the Archives d'Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence and failed (or could

not) look at those preserved in Phnom Penh's National Archives. I suppose, when

Cambodia became independent in 1953 and when the Indochinese Federation was

dissolved in the wake of the July 20, 1954 Geneva agreement, the French took

away with them the colonial archives concerning the French administrations, but

left behind all those concerning the parallel Cambodian administration itself.

And these speak volumes.

Today, the students at the Law Faculty in Phnom

Penh, re-founded in 1992 with renewed French aid, are taught the Histoire des

Institutions khmères from the description contained in the book bearing this

very title by Jean Imbert, published by the Faculty in 1961. The then Doyen de

la Faculté de Droit & des Sciences Économiques de Phnom Penh wrote what is

still regarded as a reliable classic from the Sangkum era. The future lawyers

are lectured about the formal creation of the modern khum in 1908 and instructed

that from then, every inhabitant, whatever his nationality provided he paid the

personal tax (something like Margaret Thatcher's 'poll tax'), could elect

councillors (then called kromchumnum) every four years, all electors being

eligible. The councillors would elect the mékhum from among themselves who, in

turn, selected his deputies. Originally, these were very numerous, but, as they

constituted unmanageable assemblies, they were reduced in number over the years.

The organisation of the khum was the object of numerous reforms in 1919, 1925,

1931, 1935, 1941-an indication things were not running as smoothly as hoped.

French administrators were continuously trying to simplify the intricacies and

meanderings of the bureaucracy of the metropolis they were attempting to

transplant into the Protectorate.

Jean Imbert gives students a lengthy

list of the duties of the mayors, but fails to put on centre stage clearly the

fundamentally contradictory position of the mékhum. Although they were chosen by

universal suffrage, their main obligations were those of chief policeman and

tax-collectors-by essence the responsibilities of a modern State13. Imbert does

not clearly state either that the authoritarian collaborateur Vichy régime would

have nothing to do with popular elections and simply abolished them in December

194114. Instead, khum authorities came again to be designated by the authorities

up above, and Cambodians have had to wait sixty-one more years-or two

generations-for these universal elections to be restored. This explains why

hardly anyone in this country remembers anything about the tortuous history of

Cambodian local democracy.

Khmer Chronicles, the unpublished memoirs of

Chakrey Samdech Nhiek Tioulong, a seasoned administrator who worked for four

decades in the Cambodian civil service, tells us the accurate story of the

Cambodian commune in modern times. His descriptions can be clearly documented by

the vast archival material held in the National Library.

In colonial

days, by the time the French managed to de facto transform a protectorate into a

colony, there were two parallel administrative structures in the Kingdom of

Cambodia-the French one, using French language, and the Cambodian one using

Khmer. Legal documents were translated into the coloniser's idiom for him to be

in a position to supervise everything. The fourteen provinces, reorganised in

the early 1920s, or khets, corresponded to the fourteen French Residences. In

theory, those came under the Palace and the Ministers, while in practice they

were under the close supervision of the local Résident. Since provincial

Résidents reported exclusively to the Résident Supérieur in Phnom Penh, the

entire Cambodian local administration was under the administration of the

Protectorate, and the Palace together with the Council of Ministers were

by-passed.

Tioulong underlines first that, contrary to the situation in

France or other Asian countries, like Vietnam, the commune, or khum has never

really existed in Cambodia as a living human community. Solidarity among

citizens and mutual help have always existed, though, but at the village and

pagoda levels. Natural leaders were the méphums and the pagoda achas, chosen by

a consensus of the people. For security reasons, and after centuries of

incessant wars, villages were widely scattered.

In the early decades of

the 20th Century, Troisième République France, under the influence of

Radical-Socialisme and the ideology of Liberté-Égalité-Fraternité, attempted to

fix the organisation of the Cambodian commune, supposedly modelled on the

metropolis. If the mode of election (universal suffrage) has been indeed

identical since 1908, neither the

sizes nor the two main obligations of the

mékhums (security and tax collection) have their counterpart in the French

model.

At the time, the young King Sihanouk's long and bloodless fight

for independence from the return of the French in 1945 to the formal transfer of

sovereignty on November 9, 1953, formally recognised by the international

community at Geneva in 1954, kept Norodom Sihanouk too busy in those insecure

years to think of local elections. Under the reign of the Sangkum (1955-1970),

and the democratic thrust of its doctrine, attempts at restoring local democracy

were made. The idea of simply re-instating local universal suffrage, was

repeatedly waved, local communities were verbally encouraged to elect their

representatives, but the successive governments had other priorities at the

time, like education, health and industrialisation, not to forget catapulting

the newly sovereign country onto the international scene. While all that was

needed to de done, Tioulong points out, was to simply revive the November 15,

1925 Ordonnance Royale abolished by Vichy. Unfortunately, it must be admitted

that no fundamental reform came to life, as "people failed to understand the

paramount importance of the basic personality of the commune in a democracy" he

wrote wistfully. Although people were advised to elect their local

representatives, this was never sanctioned by law. This has led to a lot of

confusion both in practices at the time and in older people's memories

today.

Lessons to be drawn from the archives

1 - The Ordonnances royales: Ordonnance Royale N. 42 of June 5,

1908:

Title I, Article 1: the Khum is the territorial and administrative

division of the Khet which is directed by a Mekhum assisted by a Khum

Council.

Title III, Article 8: All inhabitants listed on the personal tax

registers, of whatever nationality, are voters in the Khum and can take part in

the nomination of the Khum Council.

The general elections will take place on a date fixed by the Council of

Ministers. When a vacancy arises, the Mekhum will inform the Provincial

Governor, who will organize an election to select a replacement within one

month.

Article 10: The Mekhum, the deputies and the Krom-Chumnum comprise the

Khum Council. They will meet as often as necessary in the Khum Office or,

alternatively, at the house of the Mekhum. These meetings will take place at

least once every three months.

Article 11: The Khum civil servants will have the following

titles:

The Mekhum: Ponhea Reacsaphibal.

First Deputy: Chumtup Reacha.

Second Deputy: Chumtup

Sena.

Third Deputy and those of the Chumtup Pheackdey.

The Chumtup,

village chief: Chumtup Sneha.

The Chumtup, simple councillor:

Phinit Kecha.

The Group chief: Kechaphibal.

The Mekhums will have a stamp with the name of the village and province in

both Cambodian and French characters.

Among the numerous tasks of the

mayors, along with his deputies and councillors, let us just note the two that

were specific to the Cambodian context and were the cause of innumerable

difficulties thereafter:

Art. 12: Powers of the Mekhum: The Mekhum is empowered, with the aid

of the councillors and group chiefs, for the direction and the implementation of

all Khum services.

He guarantees the collection of all taxes, of which he is responsible for by

Ordonnances Royales;

Responsible for law and order, he requires the

Khum-Chumnum and the inhabitants to take in turn the day and night guards which

are necessary for the security of the Khum;

To provide evidence to the judiciary, to first prosecutors, of the arrest of

individuals accused of crimes and misdemeanors;

Seen in our Palace, in Phnom Penh, on June 5, 1908.

Vu pour

exécution

SISOWATH

Le Resident superieur

LUCE

Due to many

difficulties met by the French administration in the implementation of the 1908

O.R., a number of amendments and simplifications were introduced over the years,

and in particular by the September 24, 1919 O.R. The most complete and

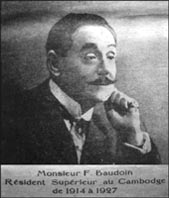

definitive description of the Cambodian commune, as defined by François

Baudouin, the "khmerophile" Résident supérieur, is to be found in the Ordonnance

Royale N° 59bis du 15 Novembre 1925. The Titre III "indicates in a more precise

manner how one should proceed with the elections of kromchumnum (the new name of

councillors) and mékhums". It simplifies the hierarchy and reduces the number of

deputies and councillors. The main objective of Baudouin was "to take into

account the evolution of the inhabitants, the transformation of the country and

the development of communal activities.

To guarantee the applicability of

the new regulations, correct errors and fill the missing gaps, the present

provisions have been the object of numerous consultations at all levels of the

Cambodian administration".

Title III, Article 11: The Kromchumnum who constitute the Khum Council

are elected by an electoral college composed of all recognized inhabitants and

French subjects older that 21 years of age, listed on the personal tax register

of the Khum or regularly exempted as retirees or invalids.

Article 14: All civil servants and administrative agents involved with

the various Indochinese budgets or Khum budgets are inelegible.

Article 17: General elections for the Khum Councils will take place

every four years. The date of the elections is to be determined in each Khet by

a decision of the Resident on the recommendation of the Chauvaykhet. These must

be announced and publicised by poster aux chefs-lieux of the Khet, the Srok and

the Khand, in the Khum Halls and in pagodas, at least two months in advance.

Article 18: All voters who want to stand as candidates for the

elections must make a written declaration and prove that they are in compliance

with tax regulations.

The following articles detail the electoral system

used. The number of councillors is proportional to the number of electors. They

have been considerably reduced since 1908 for practical reasons. There is only

one polling station in each khum, presided over by one elector and two deputies.

Polling begins at 6 am and closes at 12. Voters-men and women since 1908, it

seems-must present their personal tax card whose number is inscribed on the

electoral list. They sign it after voting. There are no official ballot papers,

but electors simply inscribe the names of their selected candidates on a piece

of white paper. (Some have been preserved and can be seen in the National

Archives). Candidates elected are those who have obtained more than 50% of the

votes. If the number of successful candidates fails to reach the required number

of councillors, one should go ahead with a second ballot from 1pm to 4pm. Only a

relative majority is then required.

The other difference with the 1908

O.R. is that it is now up to the mékum to designate his deputies or chumtup (no

more than four in the smaller communes)

As previously, the two major

duties of the mékhum, apart from what all local authorities do throughout the

world, is to be first and foremost in charge of security and the rural police,

and the collection of all locally-raised taxes. He supplies each taxpayer with

his personal tax card, which along with the identity card and état-civil

established since 1911, is the hallmark of the modern citizenry at the

time.

The Kram of December 5, 1941 decreed by the collaborating Vichy

government, which had just reneged on its written commitments to protect

Cambodian territory and handed Battambang and most of Northern part of Siem Reap

and Kampong Thom provinces to Thailand, abolished all democratic characteristics

of commune organisation.

First Article: The list of notables are made by the Chauvaysrok each

year by April 13. Those lists must be approved by the Chauvaykhet and the

Résident.

Article 28: This supercedes and abrogates all previous texts with

regard to the present Kram, notably Articles 11 to 34, 44, 57, 81 or the

Ordonnance Royale N 59bis of November 15, 1925.

To go back one full

century, one question remains to be asked: why were colonial authorities so keen

to transplant the new grassroots democratic traditions which had gradually

developed in the metropolis in the last decades of the 19th Century into a

country where the standards of literacy and education were so low? Was this not

pure utopia? There are several answers. Some given by the French administrators

themselves, some by historians later.

ï The administrators seem to have been genuinely imbued with Troisième

république democratic as-

pirations, best summarised by

the republican

motto of "Liberté-Égalité-Fraternité", and said they wished "to develop communal

activities" (François Baudouin), as we have seen. The 1908 report from the

Conseil Supérieur de l'Indochine in Hanoi notes, speaking of newly elected

councillors, that they are witnesses to

"the decentralising measure

implemented" in Cambodia15.

Historians and present day analysts claim that

these innovations expressed a desire "to achieve central control of the khum

level of administration" (David Ayres). The two views might express both sides

of a complex and ambiguous situation.

ï Proving that the centralising theory is right is that the colonising

authorities were most keen to spread peace and fight against all manner of

bandits and smugglers. They thought (exactly like today) popular mékhums would

be in the best position to promote legalised self-defence.

ï Now that Battambang and Siem Reap had been returned to the fold16, what was

of paramount importance for the authorities, was to raise as much tax as

possible from all and sundry. And as my compatriots were seized with a kind of

investing frenzy in order to cover the newly expanded Cambodian territory with a

network of roads, plantations and strikingly planned towns, not to mention a

Royal Palace-as the country had not seen since Angkorian days. And investment

was not to come from the metropolis, but had to be raised from the land.

Did elections actually take place and who voted

?

Archival material, which has been saved in Phnom Penh from

the Democratic Kampuchea years and decades of neglect, enable us to assert that

universal elections, along the lines set by the official documents did take

place from 1909 onwards till the onset of World War II.

They were never

universal in the sense that they never took place on the same day in the 14

provinces and the capital. Besides, the non-Indianised ethnic minorities of the

Northeast, or Montagnards, as the French called them, in the remote sections of

what was Stung Treng or Kratie provinces, modern local elections were

unthinkable. Therefore those were a far cry for the national character of this

weekend's local elections which are assuming a much wider political

significance. The choice of the authorities at the time was simply a practical

one: they were not in a position to control poll safety and organise the

paperwork of all these popular elections in all the khet and khum at the same

time. After the June 5, 1908 kram (or Ordonnance royale), they were first

organised at different dates in all fourteen provinces. Later, they came to be

simply held at district (srok) or khum levels, as the need was felt. And

elections were held every year till the end of the 1930s.

Official

letters (or Circulaires) from the Résident Supérieur to the provincial French

Résidents tell us that the sophisticated June 5, 1908 poll was quite

inapplicable in the long run. It was absolutely impractical to renew so often so

many councillors and notables, although there was, as in France, no limit in

time to the number of mandates those could fulfil. For instance, François

Baudouin, in a letter dated October 4, 1915, suggests the deputies could be

reduced to 1 for the khum of less than 500 inhabitants, 2 for those with less

than 1,000 and 3 for those with more than 1,000. As to the number of group

councillors, the second category (or kromchumnum), they could just be one for

each phum and one for 200 inhabitants (instead of down to 10, previously), and

no more than 3 for each phum. "Such a limitation of the number of communal

authorities would facilitate more judicious choices, make Council meetings more

easy and give a greater moral authority to elected

representatives17".

For instance, the reply of the Résident of Kampong

Chhnang is revealing, first by his approval of Baudouin's suggestions, secondly

of the contradictory desire of all democratic bureaucrats (if there is such a

thing) to both centralise the administration and promote greater people's

participation:

"...your suggestions seem to me to deserve to be followed

without modifications.[...] The figures indicated in your "circulaire" seem to

meet the two wishes of the central administration, strengthen its authority on

the one hand, and facilitate the relations between the mass of the population

and its leaders, on the other18.

One can find written evidence, in the

National Archives, that local elections did take place, district by district, or

commune by commune, till World War II. For instance, Sum Hieng, the Chanvaykhet

of Kampong Chhnang decided on June 9, 1938, that "the electoral college of khum

Andong-Snai, srok Roléa-Peir will be summoned on Friday 12 August 1938 to renew

the councillors (then called kromchumnum) in order for them to select the next

Mékhum

in replacement of Mékhum Sim who

has resigned"19.

The most

uncontroversial evidence that those local elections did take place, and that

they did not simply exist in the kram and reports of the French and Cambodian

administrators, is that we have a large number of procès-verbaux (official

reports) of these elections. They are of two kinds: the pre-1920 ones which are

very lengthy and difficult to interpret; while the latter ones are plain and

brief.

Among one of the earliest pieces of correspondence between the

Cambodian and French administrators on the subject, we can quote from the letter

of a certain Tat, Chauvaykhet of Prey Veng Province. It concerns the villages of

Peareang district:

I have the honor to acknowledge receipt of your letter No. 6 by which you

have inquired about the

meetings of the new Mekhums and Kromchumnums.

I have the honor to inform you that the Mekhums and kromchumnums which are

referred to in the proces-verbaux have good reputations and that they know how

to read and write easily in Cambodian.

January 19, 1910

We have, for

instance, the procès-verbal of the [1909] local elections in Preah Sraè commune,

Baphnom, district, Prey Veng province. The document is very lengthy for it bears

no less than a total of 534 names. Those represent in fact the full commune

electoral college. At the beginning of the list, you have the name of the

Mékhum, with his full titles, his first deputy, his second deputy, his third

deputy and the five fourth class deputies. A leading team of nine notables, all

flanked with their honorary titles!

The list is followed by the entire

electoral college, with the name of the husband in the first column, the wife in

the second, the number of children (boys and girls). In a last column simply

entitled "Observations", one is told if they are elected "Conseillers" (= first

class councillors), Kéchaphibal (that is village representative or group

leaders, that is second class members of the municipal council), or a blank,

that is simple electors.

At the bottom of each page, you have a total-but

of the children only! At the end of the report, they amount to no less than

1,533 (or an average of 5 and 6 children per family). No other addition is made.

If one adds up these lists, one comes up with 255 men and 279 women. Why the

difference? Because there are 32 widows in all. If they are on this list, does

this mean they were given the right the vote, if not to be elected? In France,

women did not vote until after World War II, in 1945. Or do I misinterpret the

procès-verbal?

If you add up the number of Conseillers and Kéchaphibal,

you come up respectively with 25 (or one for some 20 electors) and 54 (or one

for 10 electors)! One can easily understand why the Résident Supérieur concluded

that such an institution was too unmanageable and needed to be trimmed in the

future.

From the September 24, 1919 Ordonnance Royale formally

reorganising the Cambodian commune, the election procès-verbaux were more as one

might expect them to be. They no longer were electoral lists but merely spell

out the results of the vote in a particular khum.

For instance, we can look

at the December 20, 1920 elections.

Election for new Mekhum in Lovea

Sar, Srok Lovea Em

Electoral Composition

- Number of Phums: 2

Number of voters registered: 228

Number of

voters: 114

Number off Councilors to elect: 8

Results and Councilors

elected:

Chea, husband of Van, age 53, 30 votes

Khieu, husband of Man, age

37, 19 votes

Oum, husband of Khieu, age 39, 2 votes

Chhim, husband of

Oung, age 57, 5 votes

Nop, bachelor, age 31, 5 votes

Kim, husband of Kun,

age 35, 22 votes

Chea, husband of Chimm, age 33, 15 votes

Kith, husband of

Ep, age 31, 16 votes

No other candidate was voted for. These eight concilors have chosen among

them a chief who is the Mekhum, whose name is Chea, husband off Van, and the new

Mekhum of this Khum.

The new Mekhum has chosen nominees:

- Kim, as Chumtup No. 1

Khieu as Chumtup No. 2

Kith as Chumtup No.

3

Chea as Chumtup No. 4

The new notables are honest and intelligent. They can fulfill their

functions. They are quite well off.

We note that the deputies are quite

democratically selected by the Mékhum, as he nominates them exactly according to

the number of votes they each obtained. In doing so, was he obeying orders?

One cannot fail to notice that only exactly 50% of the electorate voted,

and some councillors were elected with a tiny fraction of the electorate. One

cannot draw too many conclusions for this single example, chosen at random and

simply because the paper was in quite good condition and easily readable. Local

democracy was still in its infancy-we must not forget.

The November 15,

1925 Ordonnance takes into account all the practical suggestions by the

Résidents to make these communal elections more operational, and, in the end,

one could claim, more democratic. No wonder it has remained a model in the minds

of older civil servants in Cambodia till today, like Samdech Nhiek Tioulong, in

his unpublished memoirs, or "government officials during a UNDP mission

regarding decentralisation in 1998", states Michael Ayres. To which, showing how

he ignored Cambodian administrative history, he added the comment: "-another

case of looking backwards to go forwards!"21 In reality, it could be closer to

reality to claim that the year 1925, with its Ordonnance Royale firmly

establishing (they were to last till World War II) universal local elections

represented the zenith of France's self-attributed mission civilisatrice, under

the enlightened leadership of François Baudouin.

For the leaders of

ethnic minorities-Vietnamese and Chinese in particular-the French also organised

democratic elections for them. For instance, we have the procès-verbal of the

election of the Chef des Annamites of Kampong Siem, organized by Thuom, the

Chauvayket of Kampong Cham. The vote took place in the Salakhet on May 28 1930,

from 9 am to 4pm. The ballot box was placed on a table, in the presence of the

Chauvaykhet who explained proceedings to the voters. They dropped their own

ballot papers which have been preserved to this day in the National Archives.

Out of 516 Annamite electors, 267 voted. Nguyen Van Lanh obtained 259 votes and

was therefore elected; Tran Van Buong reveived only 8 votes.

The French

Kampong Cham Résident then wired a June 13, 1930 note to Phnom Penh for the

election to be sanctioned by the Council of Ministers so that ...le candidat

proposé remplissant conditions honorabilité et solvabilité d'après

renseignements fournis par autorités indigènes, vous serais obligé vouloir

envisager dès que possible sa nomination afin de permettre de faire commencer

aussitôt le recouvrement de l'impôt personnel des Annamites dans la province de

Kompong-Siem22.

How did the democratically elected khum authorities fulfil

their duties? Were they overwhelmed by their innumerable tasks, or did they cope

and help the slow growth of communal power?

A first glance at

the National Archives not unexpectedly tell us that once the new Mékhum had been

democratically elected, the authorities kept a close eye on them. They kept

short reports on them, as a schoolmaster does for his pupils. They also

gradually instituted an elaborate system of punishments and rewards through

which the French and Cambodian administrators up above attempted to make the

Mékhum work very hard for mainly symbolic or honorary rewards-as indeed in the

metropolis-devoting much of their time to the public good. That must have proved

an immensely difficult task, but not impossible, it seems, in the Cambodian

context of the time. The best proof that the rewards were mainly symbolic, and

not really financial, was that, after the first universal commune elections of

1908-9, the French authorities found it impossible to repeat the elections at

only four years' interval. In France, on the other hand, mayors are elected

every 5 years, and their mandate can also be renewed indefinitely. They seem to

have proceeded instead very pragmatically, replacing them only when there were

resignations or any kind of difficulties. But elections did take place in some

portion of the territory every year before the onset of World War II.

Sanctions of course were proportional to the seriousness of the offence.

For instance, in December 1933, Saun Saing, the Mékhum of Kampong Chamlang,

Romdoul district, Svay Rieng, had run away to Phnom Penh with public funds. The

Sûreté was of course after him in the capital like any ordinary thief. Yet,

after taking up his post on June 14, 1929, he was noted as "conscientious, very

helpful and punctual". Later, on June 3, 1932, he was deprived of his mon-thly

allowance for "negligence in

his duties23".

A June 16, 1931 note

from the Kampong Chhnang Résident tells us a lot about what the colonisers

objected to:

I call attention to the state of Mekhums from the Srok of

kampong Tralach a certain number of particularly unfavorable appraisals of

several Mekhums:

Mekhum of Lovi: Rather intelligent but poor conduct. A

gambler who doesn't attend to his duties.

Mekhum of Sethey: Bad conduct.

Incapable. Not liked by the inhabitants. Cannot maintain his

duties.

Mekhum of Khnar Chhmor: Rather intelligent but does not have good

conduct. Works slowly. Doesn't acknowledge the presence in his Khum of

malefactors which he seems to be hiding.

Mekhum of Thlok Vien: Mekhum is

aged, with good conduct and is not strong in identifying malefactors who often

conduct raids in his Khum. He never gives information on the

malefactors.

These appreciations, which seem to have been carried out in

a very conscientious manner by the Chauvaysrok of Kg Tralach and about which you

have given advice conform, it seems to me must necessarily to undertake some

administrative measures, or judicial, of which after further study on the

question I make known to you to take without delay.

Signed: Lavit

24

This note reveals that there were limits to the sovereignty of

universal suffrage, and the tone of supervising authorities tends to be

patronising, if not condescending. Still, sanctions were not to be forthwith,

without further investigation.

A Mékhum, like Khuon from Khum Chom Chau,

Kandal, although he has an impeccable record so far, can be taken to court for

having simply supplied someone with three different actes de notoriété bearing

three different birth dates, and this without any justification25.

We

shall end this list of sanctions with the more abrupt April 19, 1915 Arrêté

Ministériel signed by Prince Sathavong, Minister of the Interior and Cult,

dismissing Mékhum Lât from Namtaov (Phnom Srok, Sisophon). He was "sentenced to

one year and six months' prison for complicity in an offence against public

decency (atttentat aux múurs) by the Sal Khet of Sisophon". The arrest is

ratified by Résident Supérieur François Baudouin26,

Conversely, when the

Mékhums perform their innumerable and tricky tasks judiciously, they receive

showers of eulogy and medals. Those can take the simple form of a brief Arrêté

ministériel expressing the gratitude of the colonial government for "the

excellent results obtained in their levying of taxation"27.

Finally, a

provincial Résident can write to the Résident Supérieur in order to suggest a

particular medal should be bestowed to a Mékhum in reward for his financial

expertise. This was the case of Mékhum Préap Ouch, from Soai Khléang, district

of Krauchmar, Kampong Cham. The Résident has personally taken note of the

perfect way he kept his civil register and his (ledger) books, together with his

ability to raise the 1932 taxes in their entirety. Besides, "by the time of the

inspection, he had already levied 80% of the 1933 taxes. Already a holder of

médaille du Roi, granted to him more than eight years before, the Résident

proposes he should now be awarded the "médaille Monisaraphon"28

On

balance, it appears the negative assessment of historians about the birth of

official local democracy has tended to be either plainly inaccurate in the claim

that the attempt was a failure and soon dropped (Chandler and Tully), or perhaps

too pessimistic in so far as it was suggested that it tended to destroy

traditional solidarities (Forest).

Is the information contained in the above descriptions

relevant to this coming Sunday's commune elections?

- It is essential for the Khmer electors and the international community to be

aware that there has been a long tradition of grassroots democracy in Cambodia.

Our international prophets of democracy are mistaken in believing they preach to

a totally ignorant congregation.

- Tax-paying women-that is the vast majority of the female population-have

perhaps voted to elect their local councillors since 1908-1909, some 37 years

before their counterparts in France, who first voted for commune elections on

April 29, 1945. Or perhaps, Cambodian archives have been misinterpreted, and

this important point needs to be checked further, incredible as this may

sound.

- The French authorities created a grassroots administrative division that

overlooked local communities around the pagodas. But, with the dramatic progress

of transport in the past century, this issue can be addressed more easily, it is

hoped. Still, one must be aware that the past two successive Communist regimes

liked this somewhat artificial commune.

- The French decided the Mékhum would be the main policeman and the main

tax-collector in his commune, two essential functions of a centralised modern

State. This was not only in contradiction to French (and European) traditions,

but it made the Mékhum's position untenable He was torn between his being both

the mouthpiece of the interests of local communities-his electors-and the local

representative of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Finance-not to

speak of the problems today raised by the centrally approved commune

secretaries.

- Since the Mékhum in colonial days was much of a tax-collector, his financial

duties were of paramount importance. The authorities were faced with two major

difficulties: first, a question of work ethics, which they seem to have been

able, if not to manage entirely, at least to contain and probably considerably

improve; secondly, a question of professional competence-or lack of it,

rather-which quite overwhelmed these almost entirely voluntary administrators.

As far as the first issue is concerned, that is the question of honesty or

corruption, it was dealt with, if not always with tact and understanding, at

least with a good measure of efficiency. The sense of public service must have

greatly increased, as the re-wards of local representatives of the people were,

to a large extent, merely honorary.

As to the second obstacle the French met-the technical difficulty of

establishing and maintaining a commune budget-the French were less successful.

There, the colonial authorities had to back down and to come up with a

compromise. After vain attempts, only larger communes, and in particular all

town khands (or quarters, districts) were in a position to keep their books, and

many of the smaller khums either never succeeded in setting up their budgets at

all or gradually gave up the attempt altogether. Finances remained in the hands

of the local chauvaysroks.

One needs to be aware that past mistakes must

not be repeated, while it has often been noted

that Cambodian history tends

to repeat itself29.

Conclusion:

Today's international experts are no less privileged

than French administrators of the past. Are the former as convinced of their

"Democratizing Mission" as the latter were of their "Civilizing

Mission"?

A leader of a democratic party told me that he was not quite

certain he liked Anwar Ibrahim's notion of a "mission démocratisatrice" and

preferred to talk of a "judicial and humanitarian mission" on the part of the

international community. But is not the search for the Rule of Law and the

promotion of human rights together with a more humane approach to politics what

the word "democracy" entails? Anwar Ibrahim's use of the word 'democratisatrice'

is more all-embracing and sums up all our aspirations-foreigners' and

Cambodians'. In deeds, not in words!

Thanks to:

I would like to thank all staff from the National

Archives in Phnom Penh for their competent and untiring help, and in particular:

Mesdames Chem Neang, Hov Rin, Y Dari, and Mr Peter Arfanis.

Henri Locard

formerly taught at the University Lumiere-Lyon 2 of Lyon in France. He is the

author of Le "Petit Livre Rouge" de Pol Pot ou les paroles de l'Angkar.

Footnote Reference:

(1) See Anwar Ibrahim, The Asian

Renaissance, pp 37-38, Times Books International:

True, the age of the

"mission civilisatrice" is over and no one talks about it any longer without a

touch of remorse or embarrassment. However, in our day, the tone is as

condescending, although it has metamorphosed into la "mission démocratisatrice".

That enterprise has acquired the status of a dogma in foreign relations, being

espoused with great sophistication, ready to be enforced with the mightiest

power known in human history.

(2) Hence the meaning also of territory or country in Khmer language

(3) See Jean Imbert, Histoire des Institutions khmères, Phnom Penh, Annales

de la faculté de Droit de Phnom Penh, 1961. I am grateful to Dr. Pidor and his

competent advice in this field.

(4) See p.118 in Alain Forest, Le Cambodge & la Colonisation française :

Histoire d'une colonisation sans heurts, (1897 1920), L'Harmatrtan, Paris, 1980.

(5) Privileges granted by the monarch to administer a certain proportion of

the kingdom for

the benefit or privilege of local mandarins.

(6) Paris, Dalloz, 1965, pp. 31-32.

(7) Monash University, Melbourne, 1999, p. 97.

(8) Ibid. pp 99-100.

(9) See p.68 in A History of Cambodia, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado,

1983, p. I56 in the first hardback edition, and p. 155 in the 1993, Thai 2nd

paperback edition.

(10) Tully's note : « ie, 'Colonisation sans heurtes' [sic] . This cannot be

adequately translated into English, but has the sense of colonisation without

clashes, shocks, bumps or bruises.

(11) Ibid. p 32.

(12) See his conclusion, p. 309.

(13) Imbert, pp. 160-161.

(14) Ibid., pp. 148-9.

(15) See the report in dossier 13 899.

(16) In 1907.

(17) See dossier N° 12 795.

(18) Ibid. Not foliated.

(19) See dossier 25 398.

(20) See dossier 16 432.

(21) The exclamation marks are David Ayres'.

(22) See dossier 9 701.

(23) See dossier 20 697.

(24) See dossier 28 895.

(25) See dossier 25 398.

(26) See dossier 14 864.

(27) See dossier 30 371, or 30 388.

(28) See dossier 25 398.

(29) Read Ros Chantrabot, Cambodge, la Répétition de l'histoire, (1991-1998),

éditions You-Feng, Paris 2000.

Contact PhnomPenh Post for full article

Post Media Co LtdThe Elements Condominium, Level 7

Hun Sen Boulevard

Phum Tuol Roka III

Sangkat Chak Angre Krom, Khan Meanchey

12353 Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Telegram: 092 555 741

Email: [email protected]