A mother watches over her son, who was diagnosed with dengue fever, at a hospital in Phnom Penh in 2013. Hong Menea

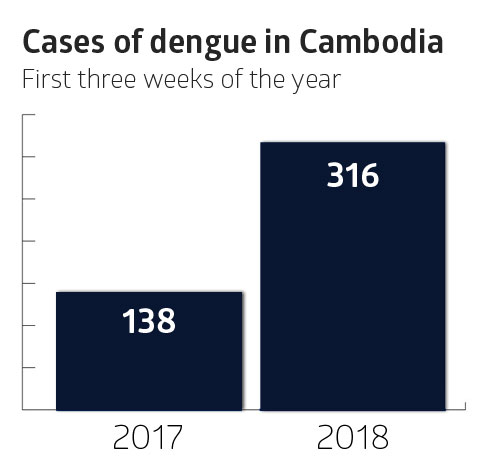

Dengue fever cases have spiked by more than 130 percent in the first three weeks of 2018 as Cambodia enters an “epidemic” year, the likes of which haven’t been seen since 2012, when the mosquito-borne virus infected nearly 40,000 and left some 160 people dead.

Dengue cases spike according to natural cycles, and health officials had predicted that another epidemic would strike the country in 2017 or this year, with this year’s number of cases already having already reached alarming rates, officials and experts said.

What’s more worrisome is that the rainy season – when virus transmission peaks – is still months away, they added.

During the first three weeks of January, there were 316 dengue cases – one of them fatal – compared to only 138 nonfatal cases in the same period last year, according to Dr Ly Sovann, spokesman for the Ministry of Health and director of the ministry’s Communicable Disease Control Department.

“We urge the public to take preventive measures and [to] go to [the] hospital for treatment,” Sovann said in a message.

Sovann and Rithea Leang, director of the National Dengue Control Program, declined to comment on the dengue fatality.

Huy Rekol, director of the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology and Malaria Control, said the death was that of a 12-year-old girl from Phnom Penh’s Por Sen Chey district.

The girl, he said, died within minutes of being admitted to the National Pediatric Hospital in January. There were only three dengue deaths recorded in all of 2017, according to Rekol, and just 18 in 2016.

Luciano Tuseo, head of the malaria programme at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Cambodia, said the mosquito-borne virus remains a public health concern in Cambodia.

“With the 5-6 year cycle of dengue outbreak and the changing pattern of dengue serological circulation over the last 3 years, the situation of dengue in Cambodia can be critical in 2018,” he wrote in an email. “The National Dengue Program is already on the alert.”

People need to take precautions, such as cleaning larva from water containers and eliminating mosquito breeding sites, as well as going to a health centre or hospital to seek treatment rather than self-medicating at home or seeking assistance at private health facilities without knowledge of dengue control, Rekol said.

The National Dengue Program has called on relevant government bodies to stock necessary medication, for hospitals to update their staff’s dengue training and for an awareness campaign to be launched for students. Sovann said whether the preventive measures will work or not will depend on the dengue program’s response and the public’s participation.

Some 6,000 litres of pesticides have already been distributed to all provinces, but should only be used as a response to eliminate outbreak clusters, he said. It shouldn’t be used as a preventive measure because the mosquitoes can build resistance.

Late last year, researchers at the Pasteur Institute – who had predicted a high risk for a Zika outbreak in 2017 in the Kingdom – said the country wasn’t fully in the clear, as the Zika virus is transmitted by the same Aedes mosquitoes that transmit dengue.

Didier Fontenille, of the Pasteur Institute, didn’t respond to a request for comment on the likelihood of a concurrent Zika outbreak.

However, Sovann said a recent mosquito survey had revealed four strains of dengue but had not uncovered the presence of Zika.

“But we monitor every day for the Zika virus and other infectious diseases,” he added.